By “Lady” Brion Gill,

Special to the AFRO

Black artists are risky. Black art shapes the reality of the Black people, counteracts harmful influences, and promotes ideals. (Sonia Sanchez)

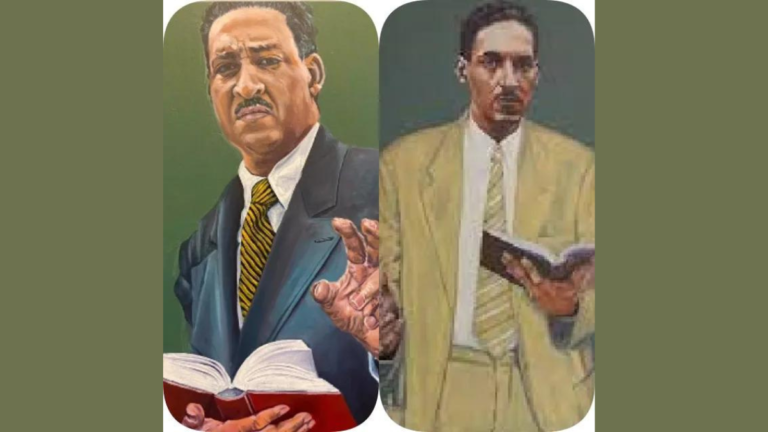

The Washington Post published an article on Jan. 6 featuring a painting of Thurgood Marshall by famous Baltimore artist Ernest Shaw. After revealing that the committee in charge of commissioning the artwork rejected the initial painting because it was too forceful, the story provoked this contemplation. I knew Ernest Shaw and checked his social media to see whether he had shared a photo of the first artwork.

When I witnessed the discrepancy between what was approved and what was denied, I couldn’t help but think of it as a metaphor for how Blackness is curated and eventually watered down in White-dominated situations.

The accepted artwork depicts a younger Thurgood Marshall with a less aggressive stance and a loose-fitting suit, indicating a less mature and less intimidating look. Black assertiveness in White-dominated environments is frequently vilified. As a spoken word artist, I know firsthand how it feels to have the Blackness in my work minimized. The Baltimore slam poetry team has been described as furious for openly criticizing racism or White supremacy in our lyrics.

My instructors and students at the University of Baltimore referred to my poems as “speeches” because the material was too radical or political to be deemed poetry. And, when I am requested to write commissioned works for institutions across the state, I am frequently instructed to “tone down” my language so that the audience feels inspired rather than uneasy.

Leaders of a Beautiful Struggle (LBS) and other groups that have been outspoken in their advocacy have faced attempts to exclude them in order to deter significant challenges to the system of White supremacy.

Art represents how various components of a society or culture handle the human experience. The subject of what it means to be human is a perennial source of cultural and political debate.

Alfonzo Peter Bailey, a writer who served as the editor of the Organization of Afro-American Unity’s (OAAU) publication “Blacklash” alongside Malcolm X, has defined all art as propaganda. He made this comment during a panel discussion on Spike Lee’s film Malcolm X in January 1993.

In outlining his concerns about the film, he said that Malcolm X was one of the few leaders throughout the 1960s to draw attention to the psychological assaults on Black people’s psyche as a result of the White supremacy system. Mr. Bailey explained how films such as Tarzan represented Africa as primitive, promoting the narrative of Black inferiority.

The idea that all art is propaganda helps to clarify what is at stake in the debate over what it means to be human. This civilization creates art–or propaganda–that contributes to the systemic dehumanization of individuals of African origin.

“Just think about how impactful a portrait like this will be for someone who has never seen themselves reflected on the walls of the halls of power….a portrait of a young attorney in the midst of his fight for civil rights will serve as a symbol of hope for all who would come to the committee in search of justice,” said state Sen. Will C. Smith Jr. in the article.

Images and representations do have power, it is true. The article then discusses the surge in Black elected leadership in Maryland. However, if the pictures most acceptable by power structures are of less “aggressive” individuals, aren’t we simply encouraging Black people not to face the system of White supremacy?

In other words, the individuals who commissioned the artwork want to make sure that we don’t promote aggressive Black people. Black people will not be free by bribing White people into include us as benefactors of their societal dominance. The art or propaganda employed to teach Black people to succumb to the White imagination’s dread of Black assertiveness has the political effect of excluding those of us who are aggressive.

The committee that commissioned the work and rejected the original picture is a metaphor for how White institutions aim to dilute Blackness. Fortunately, we have artists like Ernest Shaw who create artwork that represents Blackness as powerful and forceful throughout the area.

We must battle for such pictures to be seen to our children.

The views expressed on this website are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the AFRO. Send letters to The Afro-American • 233 E. Redwood Street Suite 600G

Baltimore, MD 21202 or fax to 1-877-570-9297 or e-mail to editor@afro.com