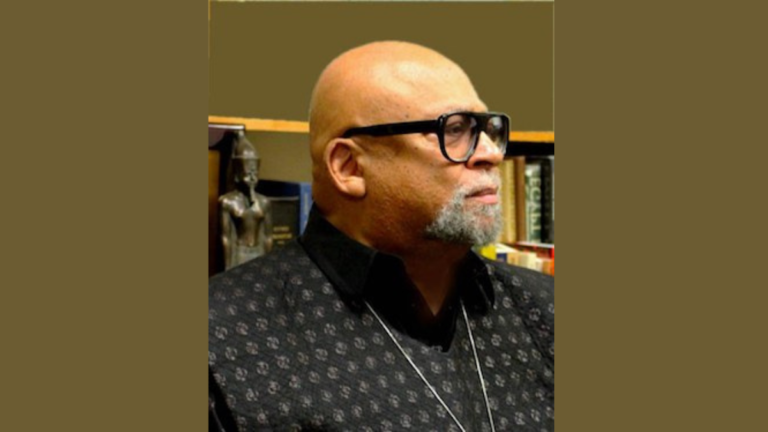

By DR. MAULANA KARENGA

(Author’s Note). The arrival of Kwanzaa each year brings us together in celebration, remembrance, reflection, and recommitment. It also encourages us to constantly study and learn the deep meanings and broad message of Kwanzaa, not only in its underlying philosophy, Kawaida, and its core Seven Principles (Nguzo Saba), but also in its symbols. Even in the midst of the pandemic, this article encourages us to do so. Indeed, as Howard Thurman taught, we must “ride the storm and remain intact,” despite the dangers, difficulties, and devastation that may befall us.

Kwanzaa was conceived as a special time and place for celebrating, debating, and reflecting on the rich and diverse ways of being and becoming African in the world. It invites us all to study its origins, principles, and practices on a continuous basis, and it teaches us, in all humility, never to claim we know everything there is to know about it, or that our explanations are only for those who are unfamiliar with its message and meaning.

Each year, we should read and reread the literature, reflect on Kwanzaa’s views and values, and engage in discussions about how it reaffirms our rootedness in African culture and brings us together all over the world in a unique and special way to celebrate ourselves as African people. One focus for such culturally grounded discussion is the deep meanings and messages embedded in Kwanzaa symbols, which are rooted in Kawaida philosophy, from which Kwanzaa and the Nguzo Saba were born. Indeed, each symbol serves as a starting point for a serious discussion about African perspectives and values, as well as the practices that are rooted in and reflect them.

The first symbol is the mazao (crops), which represent the African first-fruit harvest celebrations that Kwanzaa takes its model and essential meaning from. The mazao symbolise the harvest of good and the reward of collaborative and productive work. Indeed, the harvest concept embodies and expresses the Nguzo Saba, or Seven Principles. For the harvest’s (Nia) purpose is to bring and do good in the community and the world.

It is a goal conceived of and pursued in the spirit of unity (Umoja), self-determination (Kujichagulia), and collective work and responsibility (Ujima). Furthermore, it is created with resourceful creativity (Kuumba) and is founded on a resilient faith (Imani) that believes in, works for, and anticipates its realization. And cooperative economics (Ujamaa) accurately depicts the harvest as the product and practice of shared work and shared wealth, i.e., the cooperative creation and distribution of good.

The second Kwanzaa symbol is the mkeka (the mat), which represents our tradition and history and thus the foundation on which we build our lives, in other words, our culture. It emphasises the importance of foundation, of a cultural anchor, in order to ground and centre ourselves. We say in Kawaida philosophy that we base everything we do on tradition and reason, which means that we are constantly conversing with our culture, asking it questions and seeking answers to fundamental concerns of daily life and enduring issues of humanity.

Then, using our best moral reasoning, we choose the best solutions, the most ethical and effective way forward. The other main symbols are placed on the mkeka to emphasize the importance and indispensable role of tradition once more.

The kinara, or seven-candle candleholder, is the next Kwanzaa symbol. It represents our roots, our parent people, and our continental African ancestors. Although this includes all of our ancestors, continental and diasporan, in principle and practice, emphasis was placed at the outset on continental roots, in order to return us to the original source of our history, culture, and coming-to-be as a people. As Molefi Asante points out, stepping outside of our history is difficult and damaging to our sense of self. This is why, like Malcolm X and Mary McLeod Bethune, we emphasize a long historical conception of ourselves and the legacy of excellence left to us.

The mishumaa saba, the next Kwanzaa symbol, is held by the kinara (the seven candles). The mishumaa saba represent the Nguzo Saba, the Seven Principles, the hub and hinge around which the holiday Kwanzaa revolves, the African value system that is an essential foundation and framework for living a good and meaningful life, and the strivings and struggles that are central to this. Placing the candles in the kinara serves to remind us of the ancient culture that our principles are based on, as well as to reaffirm the timeless value of returning to the source.

And lighting the mishumaa is an ancient ritual of “lifting up the light that lasts.” For the principles are the light that endures in the midst of life’s constant and often disruptive and diversionary changes and challenges. According to the Husia, “we are given that which endures in the midst of that which is overthrown.” And what endures in the midst of what is destroyed are our moral and spiritual values. Certainly, the ethical values represented in the Nguzo Saba, both explicitly and implicitly, are among those that endure and should and must be held up as a beacon and foundation for the good life we seek to ground and build.

Another Kwanzaa symbol is the muhindi (corn), specifically ears of corn. They represent our children and, by extension, our future. The life-cycle of corn represented the life-cycle of both humans and the nature in which they are embedded in the agricultural and naturalistic understandings of African communal societies. In Zulu origin stories, for example, the cornstalk represents the ancestors or parents, and the corn represents the offspring in an eternal cycle of life, death, and rebirth. Thus, children become a form of life after death, our future unfolding before us.

There is a strong emphasis on quality parenting and collective parenthood here. Parenting is not only the responsibility of a single mother and father, but also of an extended family of other relatives and the entire community. This is the meaning of the commonly shared adage that it takes a village or community to raise a child. It also emphasizes the significance and inclusiveness of the task of raising children in the most ethical and culturally grounded ways.

The kikombe cha umoja (the unity cup) represents the fundamental principle and practice of umoja (unity), which makes everything else possible. In a ritual of reinforcing the principle and practice, the kikombe is used to drink from after a statement of unity. It is also used in the ritual of pouring tambiko (libation) in memory, honor, and appreciation of our ancestors and their legacy of excellence, which we are obligated to preserve, expand, and pass on.

The zawadi (gifts) represent parents’ labour and love, rewarding their children for commitments made and kept. These gifts should never be extravagant or used as a substitute for ourselves. They must also always include a heritage symbol and a book to reflect and reinforce our commitment to our culture, as well as to knowledge and a life of learning.

The bendera and a poster or other representation of the Nguzo Saba are the two supplementary symbols. The colours of the bendera (flag, banner) are black for our people, red for our struggle, and green for the hope and future that is fostered and forged in struggle. And the Nguzo Saba representations reaffirm their central role in our lives and struggles for the good world we all want and deserve to live in and pass down to future generations.

Dr. Maulana Karenga, Professor and Chair of Africana Studies at California State University-Long Beach; Executive Director of the African American Cultural Center in the United States; Creator of Kwanzaa; and author of Kwanzaa: A Celebration of Family, Community, and Culture and Essays on Struggle: Position and Analysis, www.OfficialKwanzaaWebsite.org, www.MaulanaKarenga.org, www.AfricanAmericanCulturalCenter-LA.org, and www.Us-Organization.org are some of the websites you can visit.