MIAMI— When Didier William was six years old, his parents liquidated most of their possessions and spent the $7,000 proceeds to flee Port-au-Prince for America. William frequently inquired about Haiti as a kid growing up in North Miami. They dismissed his inquiries by stating “nou kite tout sa dèyè” — Creole for “we’ve left that all behind.”

By ASHLEY MIZNAZI

The title of William’s biggest art exhibition, “Nou Kite Tout Sa Dèyè,” is on display at the Museum of Contemporary Art North Miami until April 16 in the neighborhood where he grew up.

“I think embedded in that title is the irony of that statement, which is that you can’t leave it behind,” William explained. “It lingers with you. It’s the very fabric of what it means to be an immigrant… the kind of entwined connection we have with the society we abandoned, which is America.”

The MOCA North Miami show, organized by Erica Moiah James, includes more than 40 pieces of Williams’ work, including some of his most recent paintings and his first 12-foot tall wooden body representing a pillar used in Vodou rituals.

“It was critical to me that his voice dominated the experience,” James explained. “As an editor, I had a light hand. I could weave those stories together, but Didier was the work’s voice.” Visitors are welcomed at the gallery’s entry by a documentary of William and his sketchbooks, which provide a feel of his process. In the broader context, William’s art emphasizes his ties to Haiti. The parts come together to form a narrative of growing up Haitian in South Florida in the 1990s and early 2000s.

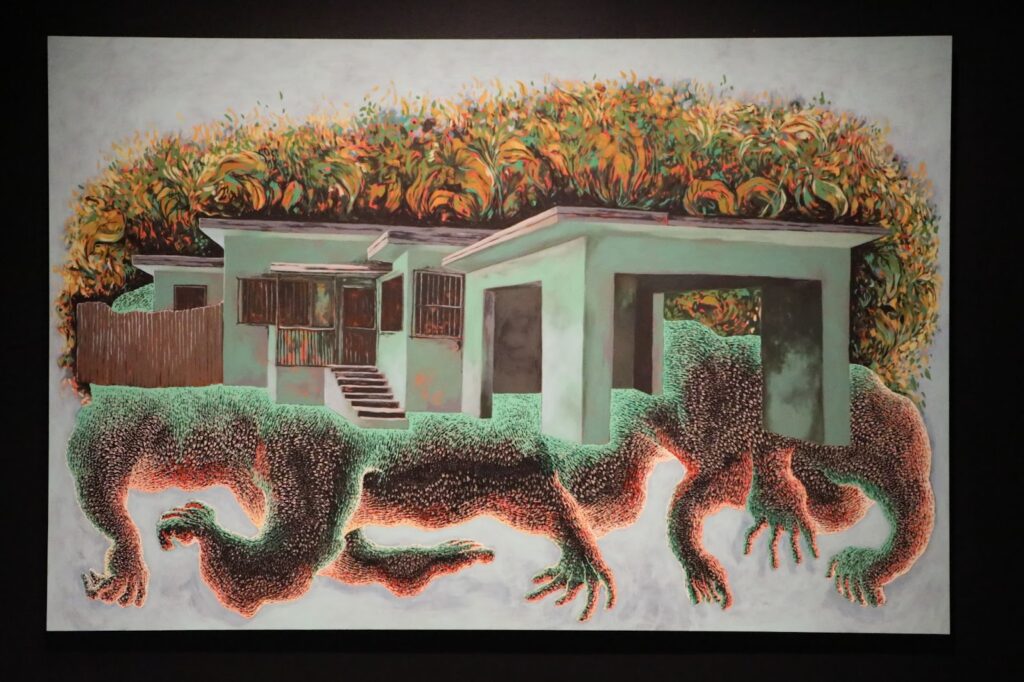

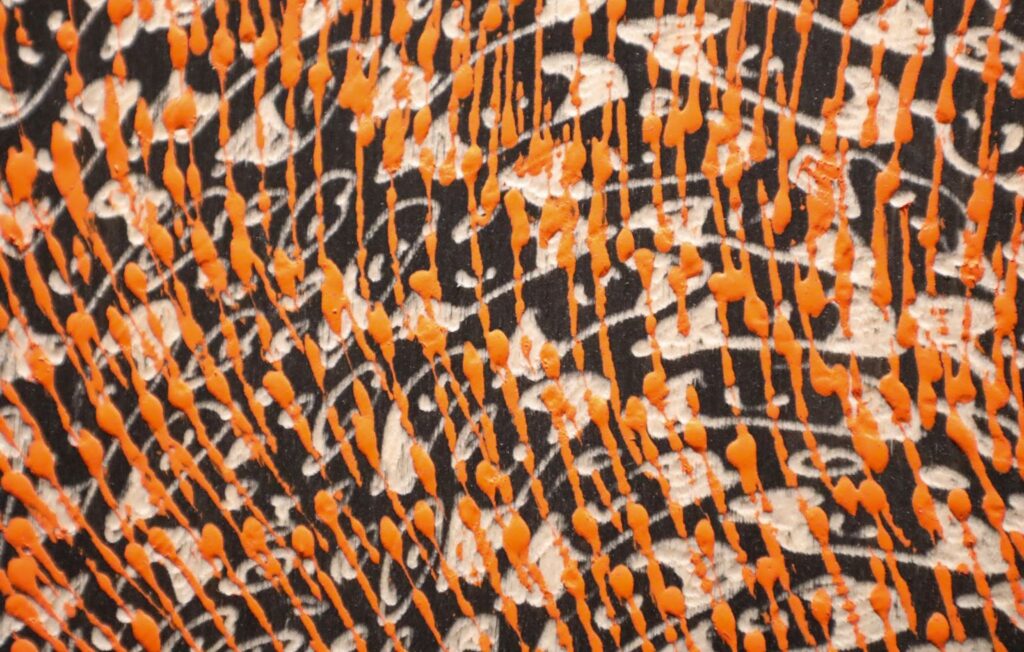

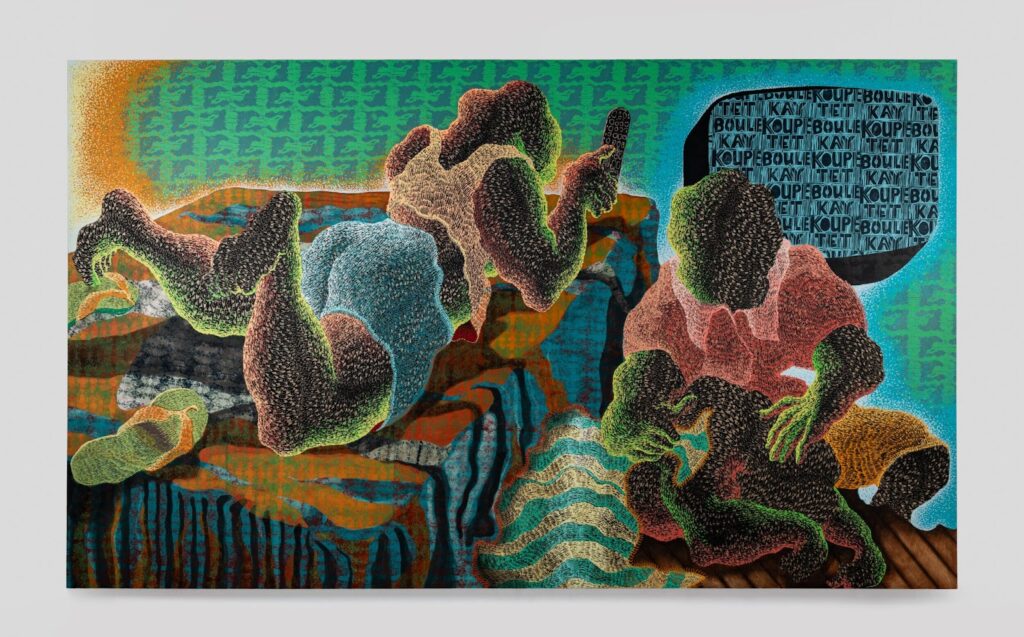

By combining printing and collage, William paints androgynous figures on wood panel backgrounds and carves eyeballs into the surfaces. His art draws on his personal link to immigrant and queer narratives, shaping the gaze felt by marginalized bodies through recollections and historical events.

William, who now lives in Philadelphia and commutes to Rutgers, is hesitant to label his art show a homecoming because of the major changes that have occurred in Miami and within himself since he departed. Art Basel was a space at a conference centre when William was in high school, and there was only one major museum downtown. He felt compelled to relocate to a place with better facilities for artists.

He received his bachelor education at the Maryland Institute College of Art in Baltimore and his doctoral education at the Yale School of Art in New Haven, Connecticut. “Now that I’ve returned, it’s incredible to see the incredible support that young Black Haitian artists are receiving in South Florida,” William said. When the 39-year-old returns to Miami, he is flooded with recollections of his early childhood events, such as learning English and having summer jobs. The MOCA North Miami is located just a few steps down from the dollar shop where he previously worked.

“I’d go across the street to Taco Bell for lunch, park very close to the museum, sit in my car, and then go back to work,” William explained. “Coming back and having a mid-career retrospective at that museum feels redemptive in some ways.” It appears that a complete circle event is taking place.”

One of Miami’s busy weekends

Between November 29 and December 4, 2022, Miami becomes a public spectacle during Art Basel, an international art exhibition that draws thousands of art aficionados, gallery owners, and buyers to the city to meet, attend conferences, and party.

The formal Art Basel Miami Beach exhibit will be held at the Miami Beach Convention Center, but there will be over 1,200 galleries throughout town, as well as other shows such as Miami Art Week and Art Miami taking place simultaneously.

Discovering oneself and one’s work

In college, William started to create work that shifted away from referencing history or telling family tales and towards more personal experiences. It got him to the place in graduate school where he could be honest about his sexuality, which opened up new avenues in his work. “I think something that is seldom discussed is that when one goes through this process of honesty with oneself, what we call coming out,” William said, “we realize that a lot of other things are buried in that closet as well.”

“I feel like so many other aspects of who I am have become freer, more honest, and liberated, allowing me to create work that I didn’t even realize was in there, many of which have nothing to do with my sexuality,” William added. “They were simply part of the concealment and burial infrastructure.” When I got out, all of those items were excavated as well.” William realized he was homosexual when he was about 12 years old, but he wasn’t ready to come out in Miami. William has married Justin William. The pair has two children: a 2-year-old daughter and a 3-month-old boy.

Art depicting significant events in Didier’s life

William granted the curator, James, complete freedom in choosing the works that would be displayed at the MOCA. It was critical for her to select not only pieces that she knew the art world would adore, but also pieces that formed a strong personal narrative, which artists frequently conceal these days.

“I admire Didier’s ability to believe in his story and himself, to believe that what he has to say is powerful, that he sees value in his story, and that he does not want to distance himself from the fullness of that story,” James said. “At the end, he said [to me] that you chose work that was extremely pivotal for me, that were turning points or where I was able to resolve an idea.”

The figurines are a key sign in William’s intricate artwork. He experimented with abstract art, pouring a lot of color, but returned to the figure after the deadly shooting of Trayvon Martin, a Black adolescent, by George Zimmerman.

In real time, William said, “I was having these kinds of conversations about the body in my studio and I was witnessing how the value of this younger way was eradicated, simply because another human being as a person looked at him with threat and looked at him with anxiety and cast his body into a particular form that allowed him to be murdered.”

The characters in William’s art are intended to be unrecognizable. They are neither masculine nor female, nor are they inherently human. “I want these figures to appear larger than life,” William explained. “These are Titans. They have personalities. They are fragments of recollections. They are not persons in the traditional meaning of the term.”

The eye is a tangible symbol of keeping testimony, representing the colonial, masculine, western, or heteronormative violent gaze that has meant life or death for Black people. What began as eyes on the bodies has evolved into eyes pervading the air around the figure.

Creole as a creative form

William gets encouragement from his folks, who have always been supportive of his objectives. His parents both served at the US Embassy in Haiti. His mother, Lucianne William, worked as a Haitian cook in the United States, and his father, Alphonse William, worked in hotel service. William recalls his parents helping him scrub poured candle wax that had gotten on the floor and making a nocturnal dash to purchase rope to complete a high school sculpture project.

“When I informed my parents I wished to be an artist, they asked, ‘How can we assist?’ When I informed my folks I was gay, they asked, “How can we assist?” said William. William grew up speaking Creole with his parents and two elder siblings, and the language is mirrored in the narratives he creates in his art. His names are frequently in Creole, and it is inscribed on his pieces. This was the first time the MOCA translated all of the wall writing giving artwork explanations into Creole.

“Putting both languages on the wall becomes yet another kind of art form and creates this sort of space of loss within the structure of a museum exhibition,” William explained. “It’s really refreshing to see art for my people and connect with the message in the paintings,” Jupshy Jazmin, a Haitian American born and raised in Miami, said on the inaugural night of the show. “Being able to see a visual of what the immigration journey may have looked or felt like in art helps bring the pieces together and what my parents and their parents have told me.”

Around 200 free prints of William’s work will be given to immigrant families in an attempt to interact with the community. “Having the people in my community with whom I grew up seeing work that mirrors and reflects their experience gives me an overwhelming sense of calm that I didn’t expect,” William said on opening night.

The Didier William exhibit will be open until April 16, 2023. Click here for a virtual tour.