By Sean Yoes, Special to the AFRO

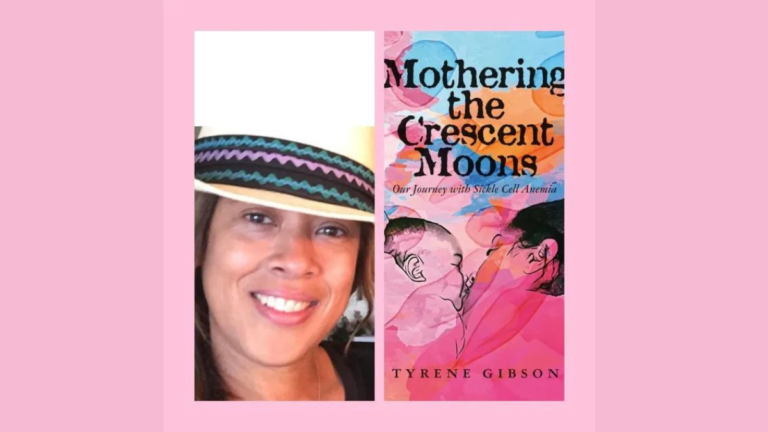

A mother’s affection is thought to be a salve that can cure all scars. When faced with a deadly disease that threatens her kid, even a mother’s devotion is put to the test. That is the center of Tyrene Gibson’s profoundly personal, heartbreaking, and eventually triumphant tale “Mothering the Crescent Moons.”

Gibson’s account of her daughter Aya Gibson Taylor’s struggle with sickle cell disease is told in the tale. (SCD). According to the Centers for Disease Control, SCD impacts millions of people worldwide, with a disproportionate amount of people with ancestors from Sub-Saharan Africa, South America, the Caribbean, and Central America, as well as other people of race. (CDC).

During a recent phone call, Gibson, who grew up in Baltimore County and now lives in New Jersey, disclosed that the sickle cell gene ran in her family. “My sibling Chiefy and I were always aware that we possessed the characteristic. I know it came from my father’s side, and I know my grandma bears the trait from my father’s line as well. “Aya’s father (Hakim Taylor) possesses the trait,” Gibson explained. As a result, it seemed unavoidable that Aya would have to start on this perilous and possibly fatal journey.

Red blood cells are usually round and flexible, enabling them to travel readily through blood arteries, according to the Mayo Clinic. However, in sickle cell disease (a collection of inherited diseases known as sickle cell disease), some of the red blood cells are formed like sickles or crescent moons. (hence the title of the book). These cells can be stiff and sticky, slowing or blocking blood movement. Other signs of SCD include anemia, excruciating pain, eyesight issues, postponed development or adolescence, hand and foot swelling, and frequent infections.

“So, I discovered (Taylor had SCD) while pregnant.” I had significant discussions with my psychiatrist about what this meant. Because…I was only aware of the characteristic; I had never experienced the illness. I’ve never had any physical problems. So I didn’t know much about it,” Gibson admitted. “Can children survive this disease?” “Absolutely,” he (Dr. Jeffrey Mazlin) said. “I wanted him to be honest and open with me, and he was, and I’m so grateful to him,” she continued. “Okay, so I had her, and she was fine.”

Taylor, despite being delivered premature, appeared so healthy that her mother began to suspect her doctor made an error with his prognosis. “She was six weeks early…but she was fine, just like any other baby,” Gibson explained. “I was hoping in my head that they had misdiagnosed her, that she didn’t actually have the disease.”

Taylor, on the other hand, was three years old when the deadly illness first attacked her. For nearly nine years, she experienced one or two agonizing pain attacks per year, as well as lengthy hospital stays for different causes linked to sickle cell disease. But, after her parents’ tireless petitioning of medical experts of all types, and then consuming vast quantities of information about sickle cell therapy, Aya was finally positioned to receive the blessing she and her family had been hoping for.

Taylor got a possibly life-saving bone marrow donation on August 1, 2012, just a few weeks before her 12th birthday, under the supervision of Dr. Jennifer Krajewski, attending physician, Department of Pediatric Stem Cell Transplantation and Cellular Therapy. “She had two rounds of chemotherapy, which destroyed her entire immune system.” “It was a pretty intense process,” Gibson said. “She’s now cured of sickle cell anemia…and lives a normal life like any other young adult.”

Yet another episode in Taylor’s journey with sickle cell disease remained to be written. This story, too, had a happy conclusion. Taylor (then 15) was able to journey to Heidelberg, Germany on July 9, 2016, to meet the guy who supplied the bone marrow that eventually destroyed the debilitating illness that had plagued her for nearly a decade.

“It was so surreal to know that somebody helped me like that,” Taylor said in an interview for the website “Tackle Kids Cancer,” a group with which Taylor, now in her early twenties, works closely as a transplant champion. “He and his lady were wonderful. They were overjoyed that I was alright. “They are now like family,” she continued. “I have a distinct perspective on life. I wouldn’t be able to do many tasks without a donation. I’d like to make the most of my existence. “Not many people are given a second chance.”

She is making the most of her second opportunity and is determined to pay it forward. Taylor is a biology student at Loyola University in New Orleans with aspirations of becoming a neonatal hematologist. That is Dr. Bruce Terrin’s expertise, and he has been crucial in Taylor’s fight against sickle cell since her mother was pregnant with her.

Gibson has been resolved to share their tale since the days leading up to Taylor’s bone marrow transplant, when she courageously endured excruciating agony. Mothering the Crescent Moons, a road plan for others negotiating the onslaught of this fatal illness, was published after years of starts and pauses.

“I started writing it when she was ten.” I began, but I stopped. Then, when the epidemic struck and we couldn’t go out much, we stayed in. “I said, you know what, I need to finish this,” said Gibson, a real estate worker, first-time author, and New Jersey representative for the Be the Match National Marrow Donor Program.

“I want to be able to help other people so that their children don’t have to suffer for the rest of their lives, or die from sickle cell or its complications,” Gibson said. And for those she wants to inspire and assist, she provides six principles.

“Never give up; if one door closes, look for another door or even a window,” she advised. “Continue to learn about new technology and developments, ask many questions, and pray.”